By Farooq A. Kperogi

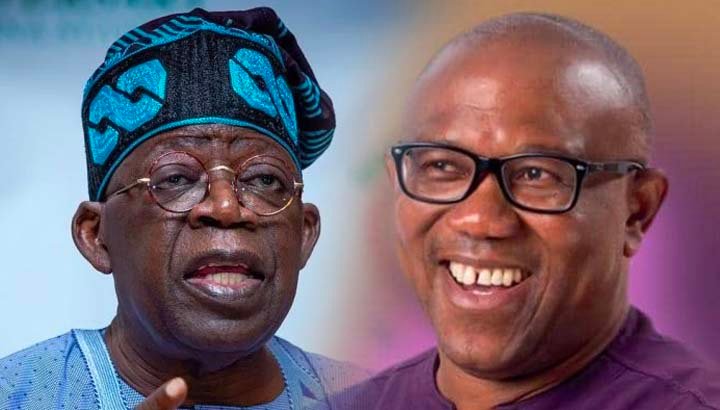

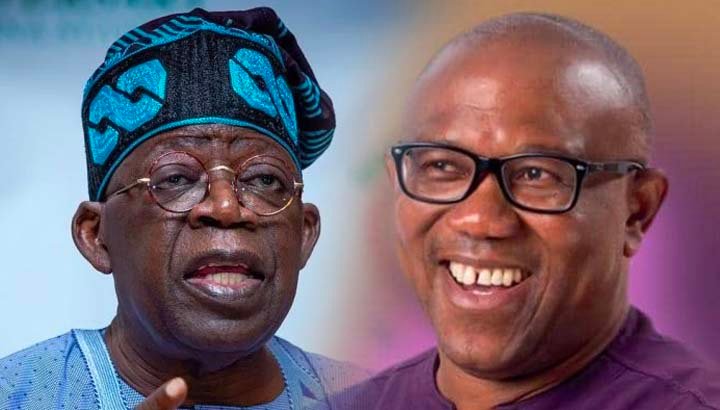

Two certainties have underpinned voting behavior in Nigeria, which APC’s Asiwaju Bola Ahmed Tinubu and Labour Party’s Mr. Peter Obi will either uphold or explode in next year’s presidential election. While one of the certainties is time-honoured, the other is more contemporary and enabled by social media.

The most time-honored fixity in Nigerian electoral politics since independence is the certitude that the Yoruba electorate will always overwhelmingly vote for a Yoruba candidate in national elective contests in which other candidates are non-Yoruba. Will Tinubu uphold, modify, or disaffirm this age-old pattern? I’ll return to this shortly.

The second fixture in Nigeria’s electoral politics since at least 2011 is the almost inexorable nexus between candidates who dominate the social media discursive arena and candidates who win the presidential election. Peter Obi is now undoubtedly the undisputed favorite in Nigeria’s social media circles. Will he replicate previous patterns?

Let’s start with Tinubu and the Yoruba voting trajectory. On the surface, it seems outrageously accusatory and unfair to say Yoruba people inescapably vote for their kind in presidential elections. But that is what the historical evidence says.

Note, however, I am not by any means saying that every single Yoruba voter has always voted for Yoruba candidates in presidential elections. I am only saying that the majority of Yoruba voters always vote for their kind.

Chief Obafemi Awolowo enjoyed the kind of political dominance in Western Nigeria that Sir Ahmadu Bello didn’t have even in Hausaphone Muslim Northern Nigeria (he could never win over Kano, for example) and that Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe didn’t enjoy in Eastern Nigeria.

Well, one can attribute Awolowo’s political iconicity in Western Nigeria to his admirable policies and inclusive strategies when he was a premier of the region. But how about Chief MKO Abiola?

Abiola spent the better part of his political career undermining Awolowo and swimming against the political mainstream in Yoruba land. His Concord newspaper was virulently and implacably anti-Awolowo.

Unlike Tinubu who used to subordinate his Muslim identity to the point of erasure until the last few years, Abiola wore his Islam on his sleeves.

He advocated the establishment of sharia in Yoruba land; built hundreds of mosques nationwide; openly supported Islamic causes in and outside Nigeria; was the Baba Adini of Yoruba land [i.e., the ceremonial head of Islam in Yoruba land); and aggressively worked for and defended Nigeria’s membership in the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC), which caused the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) in 1986 to urge Christians to boycott the Concord newspaper.

Abiola was also the victim of a vicious whispering campaign in churches that he bought hundreds of thousands of bibles and intentionally sunk them in the sea. It was false but many Christians believed it.

So, when he chose a northern Muslim running mate in 1993, like Tinubu has done, the exact same reaction as we’re seeing today from Christians followed. Northern Christians kicked, and Yoruba Christians said they wouldn’t vote for him both because of his past and his choice of a Muslim running mate.

But when his opponent turned out to be Alhaji Bashir Tofa, a Kanuri Muslim born and raised in Kano, the Yoruba electorate closed ranks, eschewed religious divisions, accentuated Abiola’s ethnicity, and voted for him overwhelmingly.

We saw a repeat of this with Chief Olusegun Obasanjo. When his major opponent was Chief Olu Falae, another Yoruba man, he lost not only the Southwest but also his natal Ogun State. However, when his major opponent in 2003 was Major General Muhammadu Buhari, the Yoruba electorate voted for him massively.

Note that Obasanjo did things that made him unpopular in the Southwest. For example, he ordered the shooting on sight of OPC members, starved Lagos of federal allocations out of spite, and actively worked to disrupt the prevailing political consensus of the region. Yet, the Yoruba political elite not only preferred him to Buhari, they also merged their political party, the Alliance for Democracy (AD), with the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) for the purpose of the 2003 presidential election, which led to the death of AD.

In a February 21, 2003, confidential cable revealed by WikiLeaks in 2011, the US Consul General reported Tinubu to have told him that Yoruba people would vote for Obasanjo against Buhari because even though Obasanjo was unlikeable, he was Yoruba and Buhari wasn’t.

The cable reads: “Turning to the presidential contest, Tinubu disclosed that he does not like President Obasanjo because he contributed to the end of democracy in Nigeria during his tenure as a military president and is now benefiting from that history.

“That said, Tinubu admitted that he and his party, the Alliance for Democracy, must support Obasanjo. Southwest Nigeria is Yoruba land and the President is Yoruba. Tinubu”s [sic] party had no choice since it has not fielded a presidential candidate. Moreover, Obasanjo is the only candidate who stands a chance of blocking his rival, General Muhammadu Buhari, whose ethnocentrism would jeopardize Nigeria”s [sic] national unity. Buhari and his ilk are agents of destabilization who would be far worse than Obasanjo….”

Tinubu and his group would later embrace the same Buhari the fear of whom had driven them to embrace and support an unlikeable Obasanjo.

If the Yoruba voting pattern that I have established is any guide, Tinubu will win the majority of votes in the Southwest in spite of the apparent religious dissension in the region now.

Should he, however, win only marginally or, worse, lose in the region, it would mean that religion, particularly Pentecostal Christianity, has finally succeeded in trumping ethnicity in Yoruba land. That would be seismic and invite a reworking of the sociology of the region, especially if Peter Obi makes significant inroads in Southwest states outside of Lagos (where Igbos constitute a significant voting bloc).

It would mean that, like in Northern Nigeria, religion has graduated to a more significant predictor of political behavior than ethnicity in Yorubaland. That would have far-reaching consequences for the mapping of the contours of the Yoruba political landscape going forward.

The second observational data that will be up for empirical corroboration or explosion in the 2023 election is the nexus between social media popularity and electoral triumph in presidential contests. I studied this systematically from 2011 to now.

In 2011, when social media was still at its inchoate stage in Nigeria, Dr. Goodluck Jonathan bestrode the social media scene like a colossus and pulverized Buhari in the election. Buhari returned the favor in 2015 after coalescing with the dominant political elites of the Southwest. Buhari dominated the social media space and ended up winning the election.

In 2019, Buhari’s online devotees lost their creative juices and left the stage for Alhaji Atiku Abubakar’s online foot soldiers. Atiku ruled the social media conversation during electioneering and went ahead to win the election but was rigged out in one of the most brazen electoral heists in Nigeria’s history. Both INEC insiders and U.S. State Department officials have confirmed that Buhari lost the 2019 election by close to 2 million votes.

The clamorousness of Peter Obi’s dominance of the Nigerian social media scene is uncannily redolent of Buhari’s 2015 social media supremacy. The temperaments of their supporters are eerily similar: like Buhari’s 2015 supporters, Obi’s votaries are aggressive, malicious, passionate, monomaniacal, worshipful in their admiration of their idol, intolerant of alternative views, self-righteous, and apt to invent easily falsifiable falsehoods to shore up their hero’s image.

Like Buharists in 2015, Obi adherents, who call themselves by the singularly headless and uninspired moniker “Obi-dient,” have succeeded in shutting out the voices of people who support other candidates with their venomous vituperative darts, although they met their match on Twitter in former Enugu State governor Dr. Chimaroke Nnamani who requited their verbal violence and caused the hashtag #ObidiEND to trend for days.

Well, although the link between social media dominance and eventual electoral triumph in presidential contests is more correlational than causational, it nonetheless points to the symbiosis between online and offline political organizing.

In other words, there’s a mutually reinforcing relationship between online visibility and offline success. For example, the exponential rise in PVC registration in the last few weeks has been attributed to the energy Obi has infused into the political process.

But should Obi fall short in 2023 in spite of dominating social media, I would attribute his social media dominance to what we call the spiral of silence in communication theory. Spiral of silence occurs when vast swaths of people self-censor themselves because they fear that a vocal minority’s shrill opinions are the dominant and only acceptable opinions.

Fear of insults and social isolation from the vocal minority keep the majority from expressing opinions that depart from the consensus of the vocal minority.

Whatever it is, the 2023 election is shaping up to be an election like no other in the history of Nigeria.